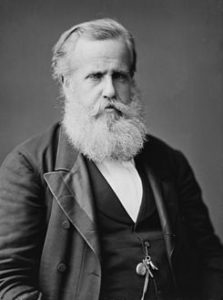

Brazil’s first and last homegrown emperor reigned for almost 60 years, more than a quarter of all of its time as an independent nation. The reign of Dom Pedro II began in 1831, less than 10 years after Brazil broke from Portugal. He went into exile in 1889 as Brazil decided a monarchy was no longer in fashion.

Pedro’s grandfather, Dom Joao, then prince regent, had fled to Brazil to avoid Napoleon’s march on Lisbon in 1807. He stayed on there after becoming king in 1816, and split Brazil from Portugal. That’s how Dom Pedro II, a descendant of Habsburg and Bourbon kings, came to be the New World’s first native born European-style monarch.

A man of a scholarly bent, he won praise from Darwin and studied the language of Brazil’s Indians. He visited the U.S. to see inventions like the telephone. Brazil’s planters forced Dom Pedro II into exile in 1889 after his daughter signed an edict accomplishing one of the king’s great goals, freeing Brazil’s slaves.

Brazilians of the 20th century seem to be fonder of their former king. There are many hospitals and public buildings now named for Dom Pedro II. Brazilians brought his body home from Europe years after he died, and buried him in the town where he had a summer home, a little more than an hour from Rio. Now named Petropolis after the emperor, the town has streets with Victorian homes. His royal summer home is now a museum. We saw no kitchen when we toured it. We wondered if there had been one in an outside building, from which servants would have brought dishes to the house.

David asked what they did when it rained, how they would prevent the emperor’s food from getting wet.

We’d had to buy umbrellas on our way to the museum. What had been a drizzle on a warm New Year’s Eve had turned into dreary rain in the days that followed.

The winding road from Rio to Petropolis was built for this kind of heavy rain. There were little channels built into the hills to divert the water. We saw several little waterfalls. I would remember the rain when I later picked up an autobiography of Chilean poet Pablo Neruda. He writes about rain in his native land was unlike “impulsivas” showers that crack like a whip in other climates and leave behind a blue sky. Southern rains have patience, Neruda wrote, and keep on falling without a break from a gray sky.

Brazil experienced unusually heavy rain during our visit. A company helping expand Sao Paolo’s subway blamed the rain for a massive hole, 30 meters deep and 80 meters wide, that opened after walls collapsed in a station under construction, according to a January report from the BBC Mundo Web site.

We ducked the rain in Petropolis with lunch at a restaurant offering a set menu. The restaurant had a name that translates to something like home cooking. After we set down our dripping umbrellas, David insisted I take the seat facing a few little paintings on the restaurant’s bright walls. A teenage girl with a nose ring slowly explained to us in Portuguese the chicken dishes available. She stopped to say good bye to us as her shift ended. Another teenager, wearing a hairnet, smiled as she brought us plates filled with tender chicken, warm black beans and white rice. The girls made sure we got the full course, including a tiny cup of the strong, sweet coffee known as cafezinho. It was one of our best meals in Brazil.