“Sometimes there’s a man, well, he’s the man for his time and place. He fits right in there.. “–lines introducing the Dude, the hero — of sorts–in the movie, “The Big Lebowski“.

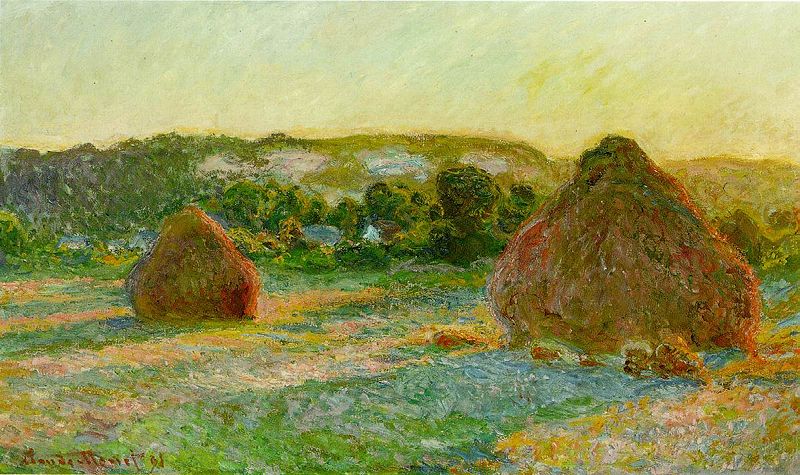

Look at the painting shown to the right. A guide at the National Gallery of Art pointed it out on a recent tour of the highlights of the museum. How well Monet captured the motion of the clouds, the grass, the wind in the clothes. He painted it outdoors, probably in a single session of several hours, according to the Web site of The National Gallery of Art, the owner of this painting.

Look at the painting shown to the right. A guide at the National Gallery of Art pointed it out on a recent tour of the highlights of the museum. How well Monet captured the motion of the clouds, the grass, the wind in the clothes. He painted it outdoors, probably in a single session of several hours, according to the Web site of The National Gallery of Art, the owner of this painting.

It took the Industrial Revolution — gritty and steeped in the soup of 19th century chemical labs — to give Monet what he needed to make such paintings. And, Monet did the Industrial Revolution the favor of seizing on its innovations and making better use of them than perhaps any other artist of his time.

The North Carolina Museum of Art did a very clever thing and put together a show on these technological advances to accompany its 2006-2007 “Monet in Normandy” exhibition. Curated by conservator Perry Hurt, the Revolution in Paint show looked at how the “birth of modern science and the Industrial Revolution in 18th century Europe supplied an unprecedented expansion in the artist’s palette.” “More than 20 intense yellow, green, blue, red, and orange pigments were invented between 1800 and 1870,” according to the show’s Web site. “The impressionists took advantage of the new pigments’ inherent chromatic and physical properties to forego the laborious techniques of traditional academic painting for a quicker and more direct painting style.”

For centuries, European painters had reserved the bluest of blues for the robes of the Virgin and others to be noted in paintings, as it was derived from the lapis lazuli stones that had to be carried in from places like Afghanistan. Suddenly, new “chemically identical ‘French’ ultramarine was dramatically cheaper, a tenth the cost, and could be afforded by even the poorest painter,” according to the Web site for “Revolution in Paint.” ‘There had never been a strong chemically stable green. Now there were three: chrome oxide green, emerald green, and viridian.”

Another innovation seems to have favored Monet. “(S)uddenly paint became portable,” said the Web site for “Revolution in Paint.” It credits the collapsible paint tube to a “frustrated South Carolina painter named John G. Rand.” “Now the impressionists could leave the studio and academic painting behind. Moving outdoors, they could seize the flickering light and capture the pulsing life around them,” the site says.

And away he went. Monet painted everything from London scenes to haystacks, and his work appears today on everything from cocktail napkins to umbrellas and t-shirts. Confessing to a fondness for Monet can almost seem as bold a choice as picking chocolate at one of those really good owner-operated ice cream parlors, like Larry’s near D.C.’s Dupont Circle, where there are all kinds of more exotic flavors and rich combinations.

Then, you get a chance to look, really look, at some of his paintings.

There was  a show some years back at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts that, if memory serves, had a room or more filled with Monet’s paintings of water lilies. It was a joy to see, just an utter joy. Looking at those paintings, as with many other Monets, revived the word “pretty” and restored it to its best meaning– that there are things in the world that seem eternally lovely without the threat of darkness, tragedy and decay that beauty demands.

a show some years back at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts that, if memory serves, had a room or more filled with Monet’s paintings of water lilies. It was a joy to see, just an utter joy. Looking at those paintings, as with many other Monets, revived the word “pretty” and restored it to its best meaning– that there are things in the world that seem eternally lovely without the threat of darkness, tragedy and decay that beauty demands.

Monet abides. I don’t know about you, to borrow a closing line from “The Big Lebowski,” but I take comfort in that.

Further reading and some fun listening…

The Big Lebowski scene from which the lines were quoted

NPR story about “The Big Lebowski”

Web site for the North Carolina Art Museum’s “Revolution” show

Monet paintings at the National Gallery of Art