It’s hard to imagine how much tribute the Inca rulers needed to build Machu Picchu. It was a city standing atop a mountain, which juts more than 1,000 feet into the air from a riverbed.

It’s hard to imagine how much tribute the Inca rulers needed to build Machu Picchu. It was a city standing atop a mountain, which juts more than 1,000 feet into the air from a riverbed.

How many farmers in what’s now Peru worked extra hours in their fields to support to make the indulgences of the Incas? Their crops were needed to feed entire classes of weavers who made the gorgeous textiles that the Incas valued more than gold. And, there were priests, and the masons who built the temples and palaces, and the ruling Incas themselves.

When it comes to agriculture, though, the Incas had some luck and seem to have made the best of this windfall. They had irrigation channels and terraces to the rich volcanic soils of their valleys more productive. The climate is surprisingly mild climates, given how high the Inca valleys rise about the sea. Machu Picchu stands more than 7,700 feet above the sea, about 50 percent higher than the U.S.’s “Mile-High City” of Denver.

productive. The climate is surprisingly mild climates, given how high the Inca valleys rise about the sea. Machu Picchu stands more than 7,700 feet above the sea, about 50 percent higher than the U.S.’s “Mile-High City” of Denver.

My husband an d I walked to the site from Aguas Calientes, the town at the base of Machu Picchu. David figures this is about the equivalent of walking up to the observation deck on the 86th floor of the Empire State Building. We did it carrying only our daypacks. Imagine doing this hauling goods for richer people and maybe leading llamas along. To the right is David on a little bridge we crossed to get to the base of Machu Picchu, and in the background is one of the mountains that Machu Picchu looks out at. The vie

d I walked to the site from Aguas Calientes, the town at the base of Machu Picchu. David figures this is about the equivalent of walking up to the observation deck on the 86th floor of the Empire State Building. We did it carrying only our daypacks. Imagine doing this hauling goods for richer people and maybe leading llamas along. To the right is David on a little bridge we crossed to get to the base of Machu Picchu, and in the background is one of the mountains that Machu Picchu looks out at. The vie w from the site really is spectacular, even better than seen in the pictures to the left.

w from the site really is spectacular, even better than seen in the pictures to the left.

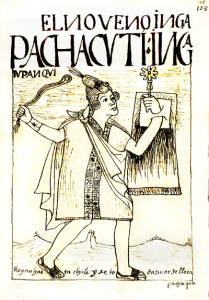

While debate continues about the purpose of Machu Picchu, there’s pretty good evidence that it was a summer palace for the Inca rulers. Berkeley professor John Rowe found a 16th century lawsuit in the archives at Cuzco filed by descendants of Pachacutec, seeking the return of a retreat called Picchu. Rowe’s students did more research and one of them is  quoted in a 2003 New York Times article as saying: ”All Machu Picchu is a big palace, the emperor’s residence across from the temple, the dwellings and workshops, everything spread out around a great plaza.” The poet Pablo Neruda imagined this city in its heyday as one where people enjoyed the finest things: “Here the fat kernels of corn were carried up and fell again to earth like red hail. Here the gold wool came off the vicuna to dress the loves, the burial mounds, the mothers, the king, the prayers, the warriors.”

quoted in a 2003 New York Times article as saying: ”All Machu Picchu is a big palace, the emperor’s residence across from the temple, the dwellings and workshops, everything spread out around a great plaza.” The poet Pablo Neruda imagined this city in its heyday as one where people enjoyed the finest things: “Here the fat kernels of corn were carried up and fell again to earth like red hail. Here the gold wool came off the vicuna to dress the loves, the burial mounds, the mothers, the king, the prayers, the warriors.”

Many histories say that the Incas had mostly abandoned Machu Picchu by the time the Spanish arrived around 1532. Perhaps an empire had to be running at its most productive to support such a place, a city on a mountain top, a hike of many days from the capital at Cuzco. Pachacutec’s successors were not effective empire builders as he had been. When the Spanish arrived, the Inca Empire had been at war within itself. Two of Pachacutec’s great-grandsons, the half brothers Huascar and Atahualpa, were using the wealth and even lives of the people within the Inca Empire in their fight to be the ruler. Atahualpa’s victory was short lived, with the waste of the war making it easier for the Spanish to gain the support of local people and topple the Inca Empire.

The Spanish were in a position to grab the Inca’s land, so incredibly rich with gold and silver because they had strong rulers at the time. Not “good” in a moral sense, considering what th ey did to the Muslim and Jewish people of Spain, but certainly Ferdinand and Isabella were effective in getting their empire going, as Pachacutec had been with his. To the right is a romanticized picture of the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella with Columbus. Ferdinand and Isabella funded his bid to open a new trade route to the Indes, which inadvertently paid off rather well. Adam Smith observed in his 1776 book, “Wealth of Nations” that “the gold and silver mines of America exceeded in fertility all those which had ever been known before.”

ey did to the Muslim and Jewish people of Spain, but certainly Ferdinand and Isabella were effective in getting their empire going, as Pachacutec had been with his. To the right is a romanticized picture of the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella with Columbus. Ferdinand and Isabella funded his bid to open a new trade route to the Indes, which inadvertently paid off rather well. Adam Smith observed in his 1776 book, “Wealth of Nations” that “the gold and silver mines of America exceeded in fertility all those which had ever been known before.”

Like Pachacutec, Ferdinand and Isabella had incompetent descendants. The Spanish monarchy managed to blow what may be history’s biggest windfall. Wars not only devoured the wealth from American mines, but disrupted shipments to Spain. Spain declared bankruptcy in 1647 and again in 1652. Despite some successes in the centuries that followed, Spain shrank back eventually into the borders first set by Ferdinand and Isabella, reduced to the majority of the Iberian peninsula. It’s kind of like a sick joke, how empires all seem to go this way, weak inheritors squandering the work of their ancestors. As with the Incas before them, the traces of Spain’s one-time American empire persist mainly in the grand buildings left behind, its New World mansions and churches like the Inca’s palaces and temples.