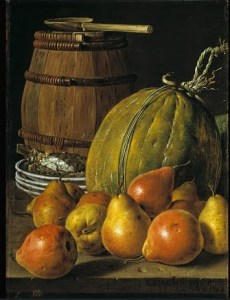

For more than two hundred years, the fruit in these two paintings has been ready to roll. It would take only the slightest tap to drop that orange from the table to the right. To the left, a single blow-out-the-candles brea

For more than two hundred years, the fruit in these two paintings has been ready to roll. It would take only the slightest tap to drop that orange from the table to the right. To the left, a single blow-out-the-candles brea th would get that pear in motion.

th would get that pear in motion.

While the artist surely didn’t intend this, the fruit seen poised at the edge of the tables reminds me of the history of its creator. Spanish artist Luis Meléndez spent his life as an artist poised for greater recognition, which he never saw.

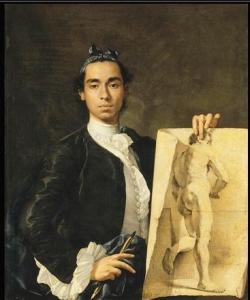

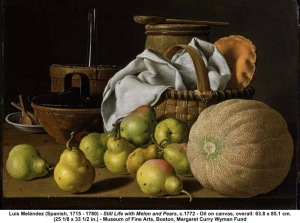

Meléndez was in his mid 50s when he received a commission from the heir to the Spanish crown, the Prince of Asturias (akin to the Prince of Wales for England), who later reigned as Carlos IV. Meléndez painted for him in the 1770s a series of still lifes about food then served commonly in Spain — chocolate, fruits, vegetables, cheese, pigeons, fish. Some Meléndez still lifes done just before he received the commission were painted on “something …like a feed sack,” , noted Catherine Metzger, senior conservator of paintings at National Gallery of Art in Washington. (She spoke in a podcast about the recent exhibit of Meléndez paintings at the museum.) That’s a marked change from the finer material he had used around age 31 for this self portrait, she said. The self portrait is “painted on a very, very fine canvas,” Metzger said. The Louvre, which owns the painting, “thinks it may even be silk,” Metzger said. At this time, his mother was still “probably financing his artistic endeavours,” Metzger said.

still lifes about food then served commonly in Spain — chocolate, fruits, vegetables, cheese, pigeons, fish. Some Meléndez still lifes done just before he received the commission were painted on “something …like a feed sack,” , noted Catherine Metzger, senior conservator of paintings at National Gallery of Art in Washington. (She spoke in a podcast about the recent exhibit of Meléndez paintings at the museum.) That’s a marked change from the finer material he had used around age 31 for this self portrait, she said. The self portrait is “painted on a very, very fine canvas,” Metzger said. The Louvre, which owns the painting, “thinks it may even be silk,” Metzger said. At this time, his mother was still “probably financing his artistic endeavours,” Metzger said.

Born to an artist and his wife in 1715, Meléndez was initially trained in miniature painting by his father, Francisco Antonio. Luis got off to a good start, studying at the provisional royal academy of art in Madrid, an institution that his father helped found. Then both Meléndez and his father were expelled from the academy in 1748. This cut off “avenues of potential patronage,” as the academy had ties to the king and court, wrote art historian Peter Cherry*. 1 Before the still life series for the Prince of Asturias in the 1770s, his most important work was helping his father in the 1750s with a commission to illuminate choir books for King Ferdinand VI.

Around 1759, Meléndez made the first of what Cherry called “four fruitless applications” to be a royal painter. 2 His biggest later success, the commission from the Prince of Asturias, lasted only about five years and was cancelled “abruptly” in 1776, according to a National Gallery biography of Meléndez. Meléndez died in 1780, shortly after declaring himself a pauper, “and his reputation sank into relative obscurity,” the biography says.

So what would have happened if Meléndez had gained fame in his time, if the pear or the orange had rolled instead of staying poised on the edge?

Historian Cherry’s verdict is …

Though he didn’t wish it, Meléndez wound up free to develop his own more distinctive approach to still life. As a result, the appeal of his work “is even stronger today for viewers whose conception of still life has been conditioned by the achievements of modern art,” Cherry said. 4

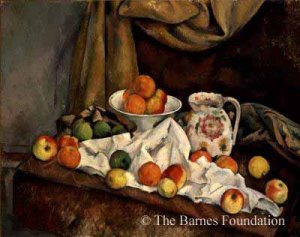

That’s certainly true. There’s something about the fruit in the still life paintings included in the National Gallery’s show that reminded me very much of the work of French painter Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), whom both Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse are credited with calling “the father of us all,” meaning modern art. Below to the left is a Cézanne still life, and to the right, a Meléndez one. Seen “in the paint,” as museum folks say about seeing the actual work, the fruit in the Meléndez still lifes has weight to it, as does fruit in some Cézanne still lifes. You want to pick up one of those pears, to feel it.

The Meléndez show has ended in Washington, but is traveling on to Los Angeles and Boston. If you happen to be in one of those cities, I highly recommend it. (This Web site has more information.) The still lifes in the show were ..delicious. I considered for a minute shelving the exhibition catalogue with my cookbooks, instead of art history ones.

Here are some of the works shown…

_____

Notes. Images of Meléndez still lifes were copied from the NGA site and Google Images. The Cézanne painting comes from the Barnes Foundation site.

The quotes, 1,2,3,4, from historian Cherry come from his essay, “Luis Meléndez : Real Life and Still Life” in the exhibition catalogue, “Luis Meléndez : Master of the Spanish Still Life.”

1. page 5

2. page. 9

2. page 27

3. page 19