I am looking at the green mountains of northern Haiti as my husband rides into my line of view.

The lush backdrop around the coastal city of Cap Haïtien is a welcome surprise. You read so much in the news about the serious problem with deforestation in Haiti, especially around the capital of Port-au-Prince in the center of the country.

Like the rest of our group of six travelers, David is a passenger on a small motorcycle, or moto. We quickly arranged this fleet of motos some miles back. David checks in with me through mutual nods, and then his driver pulls their small moto ahead of the one on which I ride.

I hope my smile tells him how happy I am at this moment.

I hope my smile is as wide and peaceful as those I just saw on the faces of our friends Janis and Lois. They each passed me a few minutes earlier on this joy ride. We’re all perched on the back of these motos with our collection of luggage, which includes five backpacks and a lar ge duffel, plus our smaller daypacks. Lois’ husband, Paul, also carries the colorful environmentally-friendly shopping bag in which Lois had put two pretty painted metal pieces she and I bought earlier. The wind ripples the bag. It’s like a merry pirate flag for our group, los refugiados, the refugees, as we will later dub ourselves.

ge duffel, plus our smaller daypacks. Lois’ husband, Paul, also carries the colorful environmentally-friendly shopping bag in which Lois had put two pretty painted metal pieces she and I bought earlier. The wind ripples the bag. It’s like a merry pirate flag for our group, los refugiados, the refugees, as we will later dub ourselves.

Much of this trip is made on open road. There’s little traffic beyond our band of six blans riding on the back of motos under the control of local drivers. Blan is the word for both white and foreigner in Kreyòl, or Creole, the primary language of Haiti. Blans are a common sight in these parts, but they tend to travel in SUVs paid for by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) or the United Nations. The UN has had a militia of sorts in Haiti since 2004. Or, it may be more accurate to say an army of foreigners. Chileans and Nepalis are among those who have served.

We look odd, a pack of blans balancing our luggage on small motorcycles shared with our drivers. From time to time, we pass school children who stare at us. I wave to a group of girls wearing school uniforms as we pass them.

Our group of six blans is nearing the end of our stay in northern Haiti, with three nights spent in the centuries-old city of Cap Haïtien. The November day is warm. The sky is a perfect mix of blue with some white clouds. The sun feels good on my face, which I usually hide from its rays behind a big hat. I look in vain from my moto to see if I can spot any sign in those green mountains of one of the world’s most amazing places, the Citadelle Laferrière.

Constructed not long after Haiti gained its independence from France in 1804, this mountaintop fortress evokes the same wonder and the same questions as does Peru’s Machu Picchu.

How on earth did people build this massive stone structure on a tall mountain, with only their own hands and a few beasts to haul the materials? Citadelle Laferrière was the vision of Henri Christophe, a man born a slave who was a leader in the Haitian Revolution and later declared himself a king. It’s a story that seems perfect for an HBO miniseries in the style of the John Adams biography, but frankly with more drama to it.

The motor bike carrying Janis’ husband Rich pulls up next to mine. He and Janis are two of my closest friends.

“The next time you ask us to go on vacation, I’m going to need to think hard on that,¨ Rich says.

We both laugh. We know immediately that this is a line that we will be telling each other for many years.

Because some miles now to the east of us, a stack of tires burns in the Haitian town of Ouanaminthe, near the border of the Dominican Republic.

Or so we have heard.

We never got close enough to the site of the protests in Ouanaminthe, pronounced Wana-meenth, to see that for ourselves. We only saw a tall plume of black smoke rising high into the sky from a distance.

Some miles away from us now to the east, people angered over a lack of basic services keep the road closed off with tree branches. They gather ready to protest what we hear are several injustices. The access to electricity is intermittent. Dominicans who cross the border to sell goods are said to get unfair privileges.

On this November afternoon, there is no obvious sign of a police presence responding to the citizens’ decision to close off a section of a main east-west road on Haiti’s north coast. The government seems to have no immediate plan that afternoon to do much more than try to let this protest sputter on its own.

Some miles away from us now to the east of us, there are shards of broken glass on the road. A bottle was shattered in a bit of theater, a negotiation tactic. It was a move meant to speed up our realization that, yes, we blans did need to pay for moto rides to carry us west away from the closed section road. We needed to do so without any further debate among ourselves. That broken bottle said that we were not getting through the blocked road to make our way east to the Dominican Republic, no matter how much we wanted to move on that day in our trip.

The street theater stepped up a notch. Some things are thrown in our vicinity before our group agreed to leave with the moto drivers. My arm will ache a bit for hours from a hit it took from either a rock or maybe a stick. I don’t know which. My eyes were closed when it happened.

¨Allez, allez, allez (go, go, go),” I whispered in my terrible French to the driver of my moto, as someone in the crowd plucked my hat off my head.

Six Dumb Blans

Trust me that the fault was entirely ours for getting anywhere near that mess on the road to Ounanaminthe.

It took quite a bit of stubbornness and determination to move ourselves away from the peace and safety of Cap Haïtien.

It took work. It took moxie. It required the “don’t take no for an answer” attitude of our group, five of whom have roots in New York. (The sixth was my husband. David is a Nebraska native who has lived in Washington, D.C. for more than 20 years. His impatience is such that he could never be successfully repatriated back to Omaha.)

We six dumb blans not only went looking for trouble, we hustled to contract private transportation for our search.

The protests near Ouanaminthe had stopped the regular Caribe Tours bus service between Cap Haïtien and cities in Haiti’s neighboring country, the Dominican Republic. To try to cross the border, our group rented an entire taptap, as Haitians call the converted pickup trucks used as the backbone of local transportation. Long benches line each side of the truck bed in a taptap. People jump on and off along normal tap tap routes, sharing those bench seats or catch a ride by standing on the back bumper.

Our rented taptap had dropped us off near the protest at our request. We mistakenly figured we would arrange new transport once we crossed through the road closure and protest on foot.

All Okay in Okap

Before we stupidly commandeered a taptap to take us into a tense situation, our time in Haiti had been a series of pleasant discoveries.

For roughly $150 a night, you can rent a room at one of the hotels in the hills above Cap Haïtien and enjoy a broad view of the harbor below. We stayed at both Habitation Jouissant and Mont Joli during our short stay in that city, and spent many hours lolling around in their well-kept pools

The food in Cap Haïtien was far better than we expected. Conch, called lambi, and other fish dishes were served with peppery sauces at lively open-air restaurants.

But, it’s the architecture in Cap Haïtien that gets the imagination going. It’s a gem in the rough, with many one-story buildings that bring to mind the French Quarter of New Orleans. There are a few grander buildings scattered here and there, including an old-fashioned public market made of iron.

Converting a few of the older buildings into restaurants might be enough to spark some bigger changes for this city. Maybe a small touristy section could draw a stream of visitors from the cruise ships that stop at the private beach at Labadee on Haiti’s north coast. That’s what you find yourself thinking as you walk the streets of this city.

Untapped Potential

Haitian leaders are trying to bring visitors and their cash to the country. The national tourism ministry in February 2015 announced a television campaign intended to attract members of the Haitian community living in greater New York and others in the region to visit. And, American Airlines in October 2014 began flying a new route, the first major carrier to connect Miami and Cap Haïtien, at least in recent years. Haiti’s president Michel Martelly was a passenger on the inaugural flight.

On Oct. 2, 2014, the nation’s No.2 official, its prime minister Laurent Lamothe tweeted ¨Cap Haitien welcomes American Airlines.¨ Lamothe is an ally of former United States President Bill Clinton, who long has been an advocate for Haiti. The forty-something Lamothe also was quoted in an American Airlines press release announcing these new flights between Cap Haïtien and Miami. Lamothe called them ¨a tremendous opportunity for significant economic impact” for Haiti.

There have been signs of progress with its tourism. Haiti’s receipts from international visitors rose to $568 million in 2013 from $162 million in 2011, according to the World Bank. But, Haiti still badly lags the neighboring Dominican Republic, with which it shares an island. The Dominican Republic had receipts from international tourism of $5.07 billion in 2013.

The World Bank estimates that about 295,000 tourists traveled to Haiti in 2012, while almost 4.6 million visited the Dominican Republic, known for its package trips to beach resorts.

In an interview with the Caribbean Journal, Lamothe said Haiti’s “potential of tourism is untapped, particularly our cultural tourism.¨ That certainly seemed true on our visit.

We flew on American Airlines to Cap Haïtien in November 2014, a month after the connection with Miami began running. The people waiting in line with us for passport stamps at the small Cap Haïtien airport fell mostly into two categories. There were Haitians returning home with large suitcases, and people from the United States traveling in volunteer groups. Many of them wore matching t-shirts about their “missions” to Haiti, usually featuring with a quote from Scripture.

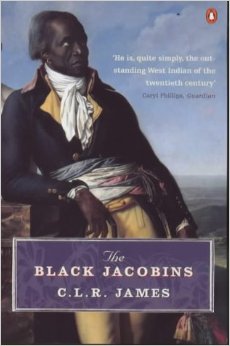

In our group of six independent travelers, there was not a Bible to be found among our possessions. But, mixed in among summer dresses and bottles of sunscreen and hiking sandals was a paperback copy of C.L.R. James’ The Black Jacobins, an excellent history on the Haitian revolution and its aftermath.

In this book, James tells of a French bourgeoisie made incredibly wealthy from the suffering of people who were enslaved in Haiti in the 18th century. He writes that some French families were rich enough to have their linens shipped across the ocean to that colony ¨to be washed, and to get the right colour and scent.¨ Their wine would make ¨two or three voyages… to give it the right flavour.¨ The historian also cataloged some of the tortures inflicted to keep the enslaved population working long days in the baking hot fields. Some people were buried alive. Others covered with boiling sugar cane. In their daily lives, the people who were enslaved “received the whip with more certainty and regularity than they received their food,” James writes.

Half of our group had already read The Black Jacobins, which did more perhaps than any other book to bring the nearly incredible story of Toussaint L’Overture to an English-speaking audience. His story remains too little known in our time.

A brilliant man who rose from slavery, L’Overture turned out to have surprising military skill that set the stage for the first nation created by people who had suffered enslavement. His work helped the people who were enslaved defeat their local masters, and then ward off attempts by France to regain control of land whose sugar had made many across the Atlantic quite rich as nearly unimaginable human costs.

Toussaint’s life seems like that of Nelson Mandela or George Washington, a case of one person who truly may have made changed the course of history in his nation. And, in the case of Touissant, the mark he left on Haiti also influenced the growth of the United States.

Yes, the mosquito gets some credit. Yellow fever took a harsh toll on French troops that fought to recapture control of what had been the prosperous colony of Saint-Domingue, as the French called Haiti. But without the skill of Touissant and his generals, the French might have bided their bid and sought to reclaim the profitable colony.

Instead, the resounding French defeat in Haiti was one of the main drivers in Napoleon’s decision to sell the United States the land that became the Louisiana purchase. That about doubled the size of the young nation. Touissant’s victories led to Thomas Jefferson’s big win.

Touissant also had talented generals who succeeded him. He was taken in 1802 to France where he died in a cell, of neglect and cold. His immediate successor was Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who would declare himself to be Haiti’s first emperor around 1804. His reign was decidedly short. After he was assassinated in 1806, control of the nation split. More cultured Paris-educated Alexandre Pétion ruled in the south, where ambitious Christophe claimed the north.

The life story of Henri Christophe inspired writers well into the 20th century. Playwrights Derek Walcott and Eugene O’Neill have used him as a subject. In the novel ¨The Kingdom of This World (1949),¨ Cuban author Alejo Carpentier writes about how Christophe rose from being a hotel worker to general to president and then king.

He also was the founder of the Citadelle Laferrière, the massive mountaintop fort that had drawn us to visit Haiti.

Into the Clouds

It was Sunday when we made our way from Cap Haïtien to the the Citadelle Laferrière. Before our trip, members of our group had spent hours online looking for a guided tour to this site. Once we got to Cap Haïtien, it was clear we didn’t need one.

Northern Haiti was far more manageable than we had thought it would be. We caught rides in crowded shared taps taps to travel about 12 miles from Cap Haïtien to Milot, the town at the foot of the ruins of Christophe’s palace, called Sans Souci.

Northern Haiti was far more manageable than we had thought it would be. We caught rides in crowded shared taps taps to travel about 12 miles from Cap Haïtien to Milot, the town at the foot of the ruins of Christophe’s palace, called Sans Souci.

The tap tap routes were busy with people heading to church services. At one point, I sat next to a man in his twenties dressed in a suit, holding his Bible. He was to speak in his church that day, he told me. We talked of how the green the trees were. That’s about all I could chat about over the noise in the crowded tap-tap, using what remains of my college French.

Once we arrived in Milot, the town near the Citadelle, we again found Haiti to be easier to negotiate than we had expected.

There had been reports of aggressive salesmanship along the steep roughly seven-kilometer climb from Christophe’s palace to his fort. At home, we had discussed whether it would be worth hiring a guide simply to help us fend off these offers.

But the people trying to sell services on the road to the Citadelle turned out to be pretty mellow, with only a few men persisting with sales pitches for horses for hire on the trail. Their offers did start coming thickly at the grounds of the ruins of Sans Souci, the palace on the outskirts of Milot. It serves as the start of the long trail up the mountain to the Citadelle. But, they trickled off fast once we were done exploring there.

If you have ever fended off offers for a camel ride near the Great Pyramid in Giza or a rickshaw in coastal Vietnam or the unsolicited hotel recommendations from a taxi driver in pretty much any poor country, you won’t be bothered much by the entrepreneurs of Milot.

Sans Souci was considered the Versailles of the Caribbean when Henri Christophe first built it. Only a few some walls remain of what once were grand buildings. A damage statue of a muse is propped near the entrance.

The one-time hotelier now turned monarch, Christophe tried to quickly build a nobility and court for himself. He even had printing presses set up.

At home in Washington, I would later find in the Library of Congress what’s said to be one of the books printed there. While the emperor had an Anglophilic streak and dubbed himself Henry Christopher, use of French persisted in his court. The book is dated to 1811 and titled “Relation des glorieux événemens qui ont porté Leurs Majestés Royales sur le trône d’Hayti; suivi de l’histoire du couronnement et du sacre du roi Henry 1er, et de la reine Marie-Louise.¨

The book describes the elaborate dress code for members of different ranks. Pour les princes et ducs, a white tunic that falls to the knee. Shoes of red leather. A hat with five red and black feathers. Pour les comtes, only three red feathers, pour les barons, two white ones. I have checked this book out a few times.

Touching its pages printed on heavy stock makes me feel connected again to our day among the ruins of Christophe’s kingdom.

Leaving San Souci, the climb to the Citadelle is tough, but worth it.

The green landscape of northern Haiti reveals itself to travelers on the path. Our group scattered walking up the long trail. I spent a few minutes with two different guides on my slow walk up the hill. French is a second language for most Haitians, with the national language of Kreyol or Creole serving as the first. These were young kids who were trying to practice their French, a little English. They told me the same things that I had already read in guide books about the Citadelle.

I gave them $5 each after we quickly exhausted my French and explained that I wanted to walk alone. I was embarrassed about my slow pace and flushed and sweaty appearance. I was sure that my face had turned a fluorescent red-pink. By that I mean the shade seen on Easter eggs dyed by children using inexpensive home coloring kits.

But up and up and up I walked into the green hills toward the Citadelle.

When the Citadelle came into view, it was a thrill. And, then it disappeared into a sudden cloud cover. While that frustrated my husband who is an avid photographer, it made the Citadelle Laferrière more magic for me. It was like something from a fairy tale, a mountaintop fortress suddenly gone from sight.

A short walk later we finally entered the Citadelle, built of stone said to be held together by mortar strengthened with cattle blood. One can spot the sea from this mountain fortress, where ornate cannons taken from European troops remain in place. The plan of the fortress is irregular, giving different views from different angles. Henri Christophe had it built out of fear that the French would try to retake Haiti. I regretted not having hired a real guide on my visit, as I had — and still have– questions about each room of the fortress. And, there were no guidebooks sold on the site.

In fact, there was no tourist schlock at all.

There were no t-shirts for sale. There were no videos, no refrigerator magnets of the Citadelle, no pens with the name of the fortress.

We couldn’t find a postcard of the Citadelle during our trip. There were none at the site or there were none anywhere we looked in Cap Haïtien. It’s possible that they are sold somewhere, but we checked at every store and every hotel we visited.

There was a small refreshment stand about midway up the trail to the Citadelle. It had packaged cold drinks on offer. Women approached our group on the road . They were selling pretty necklaces and bracelets, made of seeds and string. Imagine if those were marketed as artisan crafts of natural materials.

Having seen the Citadelle, we were ready to head onto the Dominican Republic after what we thought would be our last night out in Haiti. The city of Cap-Haïtien is pleasant to visit, even if it’s a bit scruffy.

We had dinner at the  famous Hotel du Roi Sunday night. We then returned there Monday due to the closure of the main highway near Ounaminthe. Our group of six sat on its pleasant veranda to try to figure another way into the Dominican Republic. The hotel grounds were filled with tropical plants. Polished dark wooden furniture is set clean black-and-white tiled floors.

famous Hotel du Roi Sunday night. We then returned there Monday due to the closure of the main highway near Ounaminthe. Our group of six sat on its pleasant veranda to try to figure another way into the Dominican Republic. The hotel grounds were filled with tropical plants. Polished dark wooden furniture is set clean black-and-white tiled floors.

The Hotel du Roi had a definite Graham Green vibe for those of us who are fans of that British novelist. He’s best known for his works that put Europeans and Americans in the midst of troubles erupting in poor countries like Haiti and Vietnam in the mid 20th century.

Vietnam today is a far richer place from the one depicted in Greene’s 1955 ¨The Quiet American,¨ a novel that sets the stage for the war that would erupt in that nation.

Vietnam today is a far richer place from the one depicted in Greene’s 1955 ¨The Quiet American,¨ a novel that sets the stage for the war that would erupt in that nation.

Vietnam has pulled itself into a boom of growth and prosperity, and Americans now see Vietnam as one of the safer spots for travel. About 89 percent of Vietnamese children complete at least five years of primary education, and of these, more than 90 percent continue to secondary education, according to a report from ChildFund International. UNICEF has said only four in 10 children in Haiti went to school before the 2010 earthquake, which disrupted public services there.

Haiti no longer suffers from the dictatorship of Doc Duvalier that Greene described in his 1966 book, ¨The Comedians.¨

But, it’s a country that has never in its history known long periods of sustained peaceful political stability or broad economic growth. Christophe’s rule ended abruptly in 1820. While facing a threatened invasion from a rival ruler based to the south in Haiti, Christophe suffered a stroke. He then shot himself at San Souci. His body was lugged up the mountain trail and buried in the walls of his fortress.

Lamothe, the prime minister who saw Haiti’s history as an untapped resource for tourism, had grand plans for Christophe’s castle fortress. He even posted on his YouTube channel a video about a plan to illuminate the Citadelle. But Lamothe quit his post in a December 2014 political shakeup amid violent protests.

The brief biographical sketch for his Twitter account says that he was the longest tenured prime minister for Haiti, having stayed in the job from May 2012 to December 2014. Lamothe made a failed attempt to run for president in 2015. The nation struggled to put in place a permanent successor to its last president, Michel Martelly, who left office in February 2016. An interim leader was put in place and there were plans for an April election. The Miami Herald reported in late May 2016 on the continuing drama about the still unfinished election.

Let’s hope that the next leader elected brings some stability for the people of Haiti, whom I would like to see again soon. My first trip to the country ended with our group taking those motos we hired at the protest site directly to the Cap Haïtien airport. There we found that there were six seats on a small plane leaving within an hour for the Haitian capital of Port au Prince, and a connection into Santo Domingo. It was a great bit of luck for us. As it turned out, the road we had hoped to take from Haiti into the Dominican Republic was to stay closed for many days amid protests.

I both hope and fear that there may not be much more time to quietly enjoy the Citadelle as I would like to do on my second visit. I want to spend more hours there, but this time with a guide who knows its history in depth.

If there is any justice, the spate of recent stories on northern Haiti such as this Conde Nast Traveler piece will pay off with more tourism.

For Haiti’s sake, I hope there will one day be too much commerce for my taste on the path to the Citadelle.

Let there be swarms of tourists and DVDs on offer in French, English, Spanish, Portuguese and Japanese. Let there be groups of guides dressed in the tall 18th century-style hats in which Toussaint and Henri Christophe are often depicted. Let there be stores with t-shirts of the Citadelle and knock-off copies of the garb dictated for the different ranks in the court of Henri Christophe.

If you have a romantic spirit and a love for wandering on the footpaths of history, you should get to the Citadelle sooner rather than later. Visit while you may still have a shot of having one of the world’s most splendid places to yourself for a few hours.

“Allez, allez, allez, (go,go,go)” I tell you.

___________________________________________________

Things read –and reread– on Haiti while researching this article

Alvarez, Julia. Una Boda en Haiti. 2013.

Anderson, Jon Lee. New Yorker. “Haiti Has a President.“ Feb. 17, 2016

Carpentier, Alejo. El reino de este mundo. 1949

Charles, Jacqueline of the Miami Herald. Too many articles to list Follow her at @jacquiecharles for more on Haiti.

Danticat, Edwidge. Claire of the Sea Light. 2013.

James, C. L. R. The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution. 1938.

Joseph, Raymond A. For Whom the Dogs Spy: Haiti: From the Duvalier Dictatorships to the Earthquake, Four Presidents, and Beyond. 2015

Oswald, Ted. Because We Are: A Libète Limyè Mystery. 2012.

Taft-Morales, Maureen. Congressional Research Service. “Haiti Under President Martelly: Current Conditions and Congressional Concerns.” 2015

Walcott, Derek. “Henri Christophe: A Chronicle in Seven Scenes,” The Haitian Trilogy.

Vargas Llosa, Mario. “¿Lo real maravilloso o artimañas literarias?” Letras Libres. January 2000.

Wilentz, Amy. Farewell, Fred Vodoo: A Letter from Haiti. 2013.