It took us a few minutes to find the Mermaid of Uzupis during our August 2017 visit to Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. My husband and I were on our own in that quest, where a few days earlier we had followed a stream of fellow tourists to see Copenhagen’s statue of the Little Mermaid.

The Danish mermaid appears quite sad, yet she may draw comfort from the thick crowds of her adoring fans. They know that things will work out well for the Little Mermaid by the end of Hans Christian Andersen’s tale, even if she doesn’t get her prince. Maybe that’s not a surprise to modern readers of the story. Danes for decades have enjoyed a remarkable social safety net, fostered in part by the nation’s geological windfall inheritance of North Sea oil and natural gas reserves.

There seems to be no such certainty about the fate of the beautiful Uzupis mermaid, a bronze statue created by artist Romas Vilčiauskas. This mermaid’s hair springs out from her head. Her eyes hold questions. For a visitor who’s been reading up on Lithuania, she seems to reflect the nation’s turbulent recent history.

Lithuania suffered one heck of a 20th century. The nation still wrestles with its own local guilt about the Holocaust deaths of an estimated 190,000 of its Jewish citizens, or 90 percent of that group. Writer Ruta Vanagaitė gained both enemies and new readers with her book “Us,” written with Nazi hunter Efraim Zuroff, about the participation of ordinary Lithuanians in the Holocaust, according to a December 2017 article in the New Yorker. Lithuanian participation in the Holocaust “involved a huge number of people rather than a handful of freaks, as I’d always thought,” she told the magazine.

Author Steve Stern contemplated the cultural losses due to Holocaust’s devastation of Vilnius in this 2012 blog about his time spent teaching in that city:

“It was a storybook milieu, complete with an argosy of hot air balloons overhead, and it dazzled me to the point where I forgot to miss what was missing. What was missing? Only about 1000 years of the most vibrant Jewish life to be found anywhere on the planet. It was here that the Vilna (Genius) sprang from the womb reciting Talmud, and the poets of Yung Vilne kept the printing presses busy until the plates were melted into bullets for the resistance.”

Vilnius, which shifted over time from Polish to Lithuanian and Russian control, long attracted Jewish scholars and artists from other parts of eastern Europe. The Expressionist painter Chaim Soutine studied art in Vilnius before heading to Paris, where he created works such as “Return from School After the Storm,” which the Phillips Collection owns. This painting done in 1939 can make the viewer feel dread. How vulnerable these two little figures seem. Shortly after completing this work, Soutine would flee Paris to hide from Nazis in rural France.

Back in Vilnius, the Nazi occupation emptied the once vibrant Jewish quarter of Uzupis. Some Lithuanians had welcomed the Nazis, seeing them as liberators from Soviet oppression. But Moscow quickly resumed control of Lithuania. Large-scale deportations in the 1940s sent Lithuanians to the gulag and to work camps in Siberia and the Arctic. Ruta Sepetys brings these sad stories to life in “Between Shades of Gray,” a novel based on her research into the fates of Lithuanians torn from their homes during Soviet times. Families with young children were taken in the night and put on cattle cars, often with little more than their pajamas, according to her book.

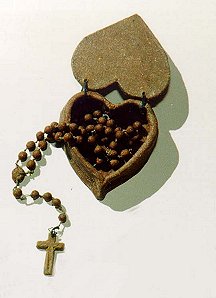

The KGB museum in Vilnius shows how Lithuanians struggled to keep faith during the deportations. On display is a rosary made from leftover bits of bread, an incredible sacrifice considering how little food many prisoners had. The museum occupies the same building where the KGB once had its local headquarters. Its exhibits show how the Soviet occupation affected many Lithuanians in their homeland. More than 1,000 prisoners were killed in the execution chamber there between 1944 and the early 1960s, according to the museum’s web site.

DILL AND OTHER DELIGHTS

As the author Stern put it in his blog on Vilnius, today it is a “beautiful city…a hard place in which to imagine the unimaginable.” There’s not one showstopper monument or site that makes Vilnius stand out. Its charms instead are more evenly spread. During our August visit, my husband and I also saw hot-air balloons lifted into the sky above Vilnus. We stopped over and over during our visit to the city to admire its handsome brick apartment buildings and old churches and attractive cafes. A small sample of these appear in the photos below.

The Jewish quarter of Uzupis has revived as the bohemian section of Vilnius. It has declared itself to be an independent republic, with its own whimsical constitution. Item No. 3 of the constitution declares: “Everyone has the right to die, but this is not an obligation.” Item No. 12 states: “A dog has the right to be a dog.”

The Uzupis mermaid sits perched on a little alcove above the Vilnia River. The river swept her away in 2004, but she was recovered and restored to her perch, according to news reports. Who knows if this will happen again? If it does, one would imagine the people of Uzupis sending out search parties armed with creative banners and mounting a lively social media campaign to seek her return. Below are some of the murals we spotted on our visit to Uzupis.

There’s actually a nicely strong hipster vibe to much of Vilnius, mixing well with its centuries-old winding streets. My husband and I started our short stay with a trip to the Snekutis cafe. An older guy with a wild mane manned the counter. He looked a lot like the subject in this portrait hanging on the wall. I wanted to ask if it was him, but didn’t. During our lunch, Iggy Pop crooned away via speakers about Miss Argentina. Bearded guys lounged around. Some of them worked here, getting up from time to time to ferry plates to tables. An old Apple sat like a dusty relic in the window. You felt that you could be anywhere with a good local scene or college-town vibe.

But you knew you were someplace offbeat and wonderful when the food arrived. My husband had a dish made with pig’s ear and his first glass of a bread-based drink called kvass. There was a sprinkling of green dill in my sour pickle soup, the first sign of an herb we’d see often in the weeks ahead on what we call our TransEurasian adventure, or our 13-nation semi-vacation of late 2017. Vilnius turned out to be our favorite stop in the Baltics.

We’d initially planned on spending only an afternoon in Vilnius, passing through the city on our way from the Lithuanian coast toward nearby Latvia. But we missed a ferry from Sweden’s Karlshamn to the Lithuania port of Klaipeda, leading us to reroute our trip. We ended up flying from Copenhagen to Vilnius, where we lingered a few days. We stayed long enough to feel possessive about this table at a little French cafe overlooking one of the most historic churches in Vilnius.

Costly Gift

An historic event took place in Klaipeda about a week before we made it to Lithuania. In late August, the tanker Clean Ocean brought the first shipment of American liquified natural gas to Lithuania, which is trying to ease itself from the grip of Russia as its energy supplier.

America in recent years has become an exporter of LNG due largely to hydrofracking. Only a few years back, the nation expected to need sizable imports of natural gas. But scarcity and high fuel prices for consumers prompted greater creativity among producers of natural gas. They increased their ability to shake loose more of the nation’s underground supply through fracking.

Advocates for cleaner forms of energy may see this as akin to a desperate person using a knife to dig the very last bits of peanut butter from a jar, the ones a spoon can’t reach. Tom Bouman explores LNG’s toll on communities in his excellent mystery novel. In“Dry Bones in the Valley,” he describes the natural history of the Appalachian Range:

“Creatures in the sea died and sank, and the mountains eroded, and over a hundred million years this mix of sediment and organic matter was buried and turned into shale, the Marcellus shale. Because of the once-living things in it, the Marcellus contains a lot of natural gas, all wrapped up in layers of rock like a present to America.”

It’s a present that comes with significant strings attached, as Bouman makes clear in his book. (It’s well worth reading. I won’t reveal its surprises here.) In the same vein, Lawrence Wright in the New Yorker called fracking “a dark bounty.” “It has created enormous wealth for some, and the flood of natural gas has lowered energy costs for many, but it has also despoiled communities and created enduring environmental hazards,” he said. Neela Bannerjee of InsideClimate News last year revealed how a pivotal EPA study on fracking downplayed the concerns of scientists.

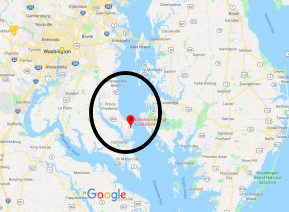

As a Washingtonian and fan of the Chesapeake Bay, I’m glad that an effective local nonprofit is keeping tabs on Dominion Energy Inc.’s plans for an LNG export site. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation has said it doesn’t oppose per se a proposed LNG site at Cove Point, Maryland.

“Our concerns for the cumulative impacts of natural gas development do, however, call for a thorough and region-wide assessment of impacts from drilling and the subsequent natural gas distribution system,” said the foundation, of which I’m a supporter.

INTERNATIONAL POWER POLITICS

Yet, some Lithuanians see the expanded U.S. supply of natural gas as quite a blessing.

LNG shipments are giving countries long dominated by Russia leverage in energy bargaining. Lithuanians deliberately gave the name Independence to their new floating LNG storage vessel at Klaipeda. The project’s “mere existence” let Lithuania negotiate its first-ever gas price discount with Gazprom, Agnia Grigas, the author of The New Geopolitics of Gas (Harvard University Press, 2017), wrote in Foreign Affairs . While Norway’s LNG reached the Lithuanian market first, the shipment from the U.S. “may hold more significance in the long term,” Grigas wrote.

“Its delivery signals that the United States is now a powerful global gas supplier and that American companies are willing to compete even in Gazprom’s most traditional markets,” she wrote.

Natural gas long played second place, or even an almost understudy role, in the global energy debate. It largely was bound to pipelines for delivery, while oil moved in great ships as well as in those underground channels. In recent years, companies and nations have invested in making natural gas more nimble.

Cooling natural gas to around -260 degrees Fahrenheit shrinks the valuable fuel to liquid form for transport. It’s often said this reduction is akin to making a beach ball the size of a ping pong ball. After it reaches its new market, LNG is warmed up and allowed to expand again like a genie freed from a bottle. Domestic exports of LNG averaged 1.9 billion cubic feet per day in 2017, 1.4 Bcf/d higher than in 2016, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. EIA said. New LNG terminals are under construction in Georgia, Texas, and Louisiana, in addition to the Cove Point project in Maryland. The nation’s key LNG export site, Sabine Pass terminal near the Texas-Louisiana border, is running at near-full capacity, EIA said.

It was a Cheniere Energy Inc. business deal, and not a government pact, that brought the LNG from Louisiana’s Sabine port to Lithuania’s Klaipeda, an American official in 2017 told Natural Gas World. “The US government was not involved in this specific deal,” Howard Solomon, deputy chief of mission at the US embassy in Vilnius, is quoted saying in the article.

Still, there’s been great interest from American lawmakers in LNG shipments to Russia’s neighbors. These exports will “strengthen our diplomatic hand when dealing with countries like Russia that like to use their energy resources as weapons,” said House Energy and Commerce Chairman Greg Walden, an Oregon Republican, at a January 2018 hearing. His powerful committee is pushing to change federal laws in order to increase the flow of LNG exports from the United States. The top Democrat on his committee, Rep. Frank Pallone Jr. of New Jersey, objects to the measures that Walden supports, including a bill (HR 4605), titled Unlocking Our Domestic LNG Potential Act.

If enacted, this bill would clear the way for exports of LNG without prior approval from the Department of Energy and would remove longstanding consumer protections, Pallone said. “As a result, the public would not have an opportunity to know about or provide input on natural gas exports to any country at any level,” he said at the January Energy and Commerce subcommittee hearing on efforts to expand LNG sales.

Yet, two of Pallone’s fellow Democrats were early backers of this bill. Among the five original cosponsors of HR 4605 are Reps. Tim Ryan of Ohio and Henry Cuellar of Texas. Both men serve on the Appropriations Committee, a natural home in Congress for pragmatists and dealmakers. And a former Senate Democratic appropriator Mary L. Landrieu of Louisiana was one of the most ardent champions of expanding LNG exports, arguing a need for it even beyond her state’s parochial interests.

LNG exports could be“a powerful geo-political tool, particularly in light of Russia’s illegal aggression” in Ukraine, Landrieu said at a 2014 Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee hearing.

As that panel’s chairwoman, Landrieu invited Lithuania’s energy minister as a witness to this hearing about increasing energy exports. Then Lithuanian Energy Minister Jaroslav Neverovic urged the senators to ease restrictions on U.S. LNG imports, arguing it would help nations now captive to Russian supply. Russia’s Gazprom had in the past cut off supply of natural gas to Ukraine, citing concerns about unpaid bills. Others saw this disruption of gas supply as a result of Russian leader Vladimir Putin’s displeasure with an Ukrainian government that sought to more closely ally itself with the West.

“The present situation in Ukraine has taught us one lesson,” Neverovic said. “No nation should be able to use its monopolistic energy supplies to punish any other nation.”

Neverovic also told the panel about the progress made on the Independence LNG import terminal, which some Americans see as a chance to build a new market for the nation’s natural gas.

“The last thing Putin and his cronies want is competition from the United States of America in the energy race,” she said. Landrieu said in her opening statement for the hearing.

In August 2017, Lithuania’s Foreign Affairs Minister Linas Linkevičius celebrated as the tanker Clean Ocean arrived at Klaipeda. “#US & #LT strategic partnership stronger every day. 1st #LNG shipment from US arrives today in Klaipėda. Crucially important for whole region,” tweeted Linkevičius, who also earlier served as his nation’s defense minister and as its representative to NATO.

Linkevičius may have a little more clout than one would expect for a minister of a country with a population of about 2.8 million. He’s very well spoken in English and understandably hawkish about the Russian threat for former Soviet republics. Linkevičius appeared in recent years on programs such as the BBC’s Hardtalk to discuss the Russian involvement in Ukraine. In trying to explain the regional threat, he told Politico about seeing Soviet tanks roll into Vilnius in 1991 to crush independence protests.

“Russians were here as a Soviet army,” Linkevičius is quoted saying. “But they were Russian troops and they were invading us, so the last thing we are on this subject is naive.”

Relations between Russia and Lithuania remain uneasy. The Economist in 2015 reported that Russia was investigating the “desertions” of Lithuanians who failed to complete their military service to the Soviet Union in the 1990s.

“25 years on, Lithuanians wonder why Russia would try to reopen a case involving a country that no longer exists,” the Economist said, referring to the U.S.S.R. “Nobody in Vilnius doubts that the timing is linked to the international situation. Lithuania has been one of Ukraine’s staunchest supporters(.)”

Russia appears unlikely to placidly allow expansion of American LNG sales into its neighborhood and its customer base, particularly when its leaders seems to want to regain some form of control of those lands. Putin’s “unabashed desire to recover territories that became independent after the fall of the Soviet Union is a threat to European security and to American leadership,” Bruce Goldwyn, a former State Department official who then was a scholar with the Brookings Institution, told the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee at the 2014 hearing on energy exports.

Power politics between the United States and Russia took a strange turn in late January 2018, when a tanker brought LNG from Putin’s nation into a Massachusetts port. The Boston Globe accused RT, a news organization backed by the Russian government, of taunting with its headline- “Sanctions anyone? US receives Russian LNG shipment, 2nd tanker reported on its way”

The shipment raised questions about the trade restrictions placed on Russian. The United States in 2014 imposed sanctions intended to weaken Russia’s energy sector after Russia annexed a chunk of Ukraine, known as Crimea. The Washington Post explained that these sanctions block financing for projects belonging to Novatek, Russia’s biggest independent producer of natural gas, but not the purchase of this fuel from Yamal, a giant company-run project in northern Siberia.

Still, the delivery outraged Ukrainian-Americans, according to the Globe. It cites Peter Woloschuk, who writes about Boston’s Ukrainian-American community, as pointing out that a local nonprofit sends about $100,000 a year in surgical supplies to Ukraine. Massachusetts hospitals have helped treat victims of “Russian aggression,” yet the controversial LNG shipment into Boston would result in sending “money to Russians and a Russian government that’s going to be used to create more victims,” Woloschuk says in the Globe article.

“How is it that our government hasn’t spoken up?” Woloschuk asks.